Moving to vanilla Emacs

Introduction

After years of daily-driving Doom Emacs, I wrote about my Doom configuration not long ago. That article was meant to be a snapshot of a mature setup, but writing it forced me to confront something I had been avoiding: I no longer understood large parts of my own editor. Doom had become a black box with my customizations bolted on top.

So I started over. Not with another distribution, but with a blank

init.el and a clear goal: build something minimal, fast,

and entirely mine. This post walks through the interesting parts of my

vanilla Emacs config (5570fb3), explaining the design decisions and

what I kept, discarded, or improved from Doom.

I. Why leave Doom

Doom Emacs is excellent software. It gave me a productive Emacs environment from day one, and its module system is genuinely well-designed. Doom is already lightweight compared to other distributions, and its modular config makes it even lighter, you only enable what you actually use.

But after years of customizing, I realized the issue was not with Doom. It was with me. I love tweaking my config, shaping it around my personal workflows, and endlessly refining how things work. My config had grown into hundreds of lines of overrides, workarounds, and hooks layered on top of Doom’s defaults. Disabled packages, patched keybindings, suppressed features. I had accumulated so much custom code that I was effectively maintaining my own framework on top of someone else’s framework. At that point, the abstraction was not helping anymore.

Doom is probably better suited for someone who wants something clean, fast, and productive out of the box, without spending hours tuning every detail.

What pushed me to start over was a desire for understanding. I wanted to know exactly what every line in my config does, why it is there, and what happens when I remove it. With Doom, debugging meant tracing through layers of macros, deferred loading, and module interactions that I did not write. With a hand-rolled config, the answer is always in my own code.

The other factor was Emacs itself catching up. Emacs 29+ ships with

Eglot, tree-sitter, project.el, and use-package built in. Many things

that justified a framework in 2020 are now just a

(use-package ...) block away. In my experience, the gap

between “vanilla Emacs” and “a productive setup” has shrunk a lot.

The goal was not to replicate Doom. It was to strip everything back to only what I need, nothing more, and understand every bit of it.

II. Config structure

The configuration lives in ~/.emacs.d/ with a flat

module structure:

early-init.el, performance settings, fonts, GUI strippinginit.el, bootstrap, core settings, module loadinglisp/, one file per concern, all prefixedsw-(smallwat3r)elpaca-lock.el, package lock file for reproducibility

Each module in lisp/ handles a single concern:

(require 'sw-theme)

(require 'sw-evil)

(require 'sw-modeline)

(require 'sw-completion)

; ...This is deliberately simpler than Doom’s module system. No

config.el vs packages.el split, no

modulep! guards, no autoload directory. Each file is a

plain Emacs Lisp module that provides its own feature. Every module in

that list is something I actually use.

All custom functions and variables share the sw- prefix,

keeping the namespace clean and greppable.

III. Elpaca over Straight.el

Doom uses Straight.el for package management, wrapped in its

own CLI (doom sync, doom upgrade, etc.) for

managing dependencies and rebuilding packages. It works, but Straight.el

is synchronous and the whole system is highly coupled.

I switched to Elpaca, a more modern package manager that installs packages asynchronously and has a simpler mental model:

(defvar elpaca-installer-version 0.11)

(defvar elpaca-directory

(expand-file-name "elpaca/" user-emacs-directory))

(defvar elpaca-lock-file

(expand-file-name "elpaca-lock.el" user-emacs-directory))The lock file (elpaca-lock.el) pins every package to a

specific commit, so a fresh clone gets the exact same versions. Doom and

Straight.el also provide version pinning, but Elpaca feels more

forward-thinking in its approach.

Elpaca integrates with use-package through a single mode

toggle:

(elpaca elpaca-use-package

(elpaca-use-package-mode))

(elpaca-wait)

(setq use-package-always-defer t

use-package-always-ensure t

use-package-expand-minimally t)The use-package-always-defer t is important. It means

every package is lazy-loaded by default, unless explicitly marked

:demand t. Combined with the custom hooks described below,

this keeps startup fast without manual :defer annotations

on every block.

IV. Startup performance

Doom already has excellent defaults for startup performance, and is one of the best frameworks in this regard. But with a hand-rolled config, you have full control over the loading sequence and can be surgical about what runs when.

My current startup time is around 0.3s without the daemon (Fedora 43), which makes it feel almost instant, and even faster with the daemon.

a) GC and file handler tricks

The early-init.el sets gc-cons-threshold to

the maximum value, which prevents Emacs from running garbage collection

(GC) while loading init files. GC pauses during startup are wasted time

since all the allocated memory is still in use. It also temporarily

clears file-name-handler-alist, the list of regex handlers

Emacs checks on every file operation (for compressed files, TRAMP,

etc.). During init, none of these are needed, and skipping the regex

matching on every load and require adds

up:

(setq gc-cons-threshold most-positive-fixnum

gc-cons-percentage 0.6)

(defvar sw-file-name-handler-alist file-name-handler-alist)

(setq file-name-handler-alist nil)

(add-hook 'emacs-startup-hook

(lambda ()

(setq file-name-handler-alist

sw-file-name-handler-alist)))After startup, we need to restore sensible GC behavior, but Emacs’

default threshold (800KB) is too aggressive for a modern config and

causes frequent pauses during normal use. GCMH solves this by

raising the threshold while you are active (64MB here, high enough that

GC rarely fires mid-keystroke) and only collecting when Emacs is idle.

The auto delay adapts based on how long GC actually takes,

scaled by the delay factor:

(use-package gcmh

:hook (sw-first-buffer . gcmh-mode)

:custom

(gcmh-idle-delay 'auto)

(gcmh-auto-idle-delay-factor 10)

(gcmh-high-cons-threshold (* 64 1024 1024)))The result is that you never notice GC happening. It runs when you pause to think, not when you are typing or scrolling.

b) Deferred initialization hooks

This idea is borrowed from Doom, which has similar hooks for staging initialization. Three custom hooks defer work until it is actually needed:

(defvar sw-first-input-hook nil

"Transient hook run before the first user input.")

(defvar sw-first-file-hook nil

"Transient hook run before the first file is opened.")

(defvar sw-first-buffer-hook nil

"Transient hook run before the first buffer switch.")Each fires once and then removes itself. The triggers are registered after startup:

(add-hook 'emacs-startup-hook

(lambda ()

(add-hook 'pre-command-hook #'sw--run-first-input)

(add-hook 'find-file-hook #'sw--run-first-file)

(add-hook 'window-buffer-change-functions

#'sw--run-first-buffer)))Most packages hook into these rather than loading eagerly. For example, Vertico defers until first input, diff-hl until first file, show-paren until first buffer:

(use-package vertico

:hook (sw-first-input . vertico-mode))

(use-package diff-hl

:hook (sw-first-file . global-diff-hl-mode))

(add-hook 'sw-first-buffer-hook #'show-paren-mode)This keeps the init sequence tight. Emacs starts, shows the dashboard, and only begins loading the completion stack, syntax highlighting, and other heavy features when you actually interact with it.

c) Native compilation and rendering

A few other settings help with runtime performance. Native

compilation (native-comp-jit-compilation) compiles Elisp to

native code in the background as packages are loaded, making subsequent

runs faster. Disabling bidirectional text reordering removes per-line

overhead that is unnecessary for left-to-right languages. And skipping

fontification during rapid input prevents Emacs from re-highlighting

syntax while you are typing, which keeps things smooth in large

files:

;; JIT native compilation, silent warnings

(setq native-comp-async-report-warnings-errors 'silent

native-comp-jit-compilation t)

;; Disable bidirectional text for left-to-right languages

(setq-default bidi-display-reordering 'left-to-right

bidi-paragraph-direction 'left-to-right)

(setq bidi-inhibit-bpa t)

;; Skip fontification during rapid input

(setq redisplay-skip-fontification-on-input t)V. Visual philosophy

My philosophy here is: show nothing unless it earns its place. No fringe, no scroll bars, no menu bar, no tool bar. The frame is maximized with 1px window dividers and nothing else. This might not be for everyone, but it helps me focus on only one thing: the actual code.

a) Theme and fonts

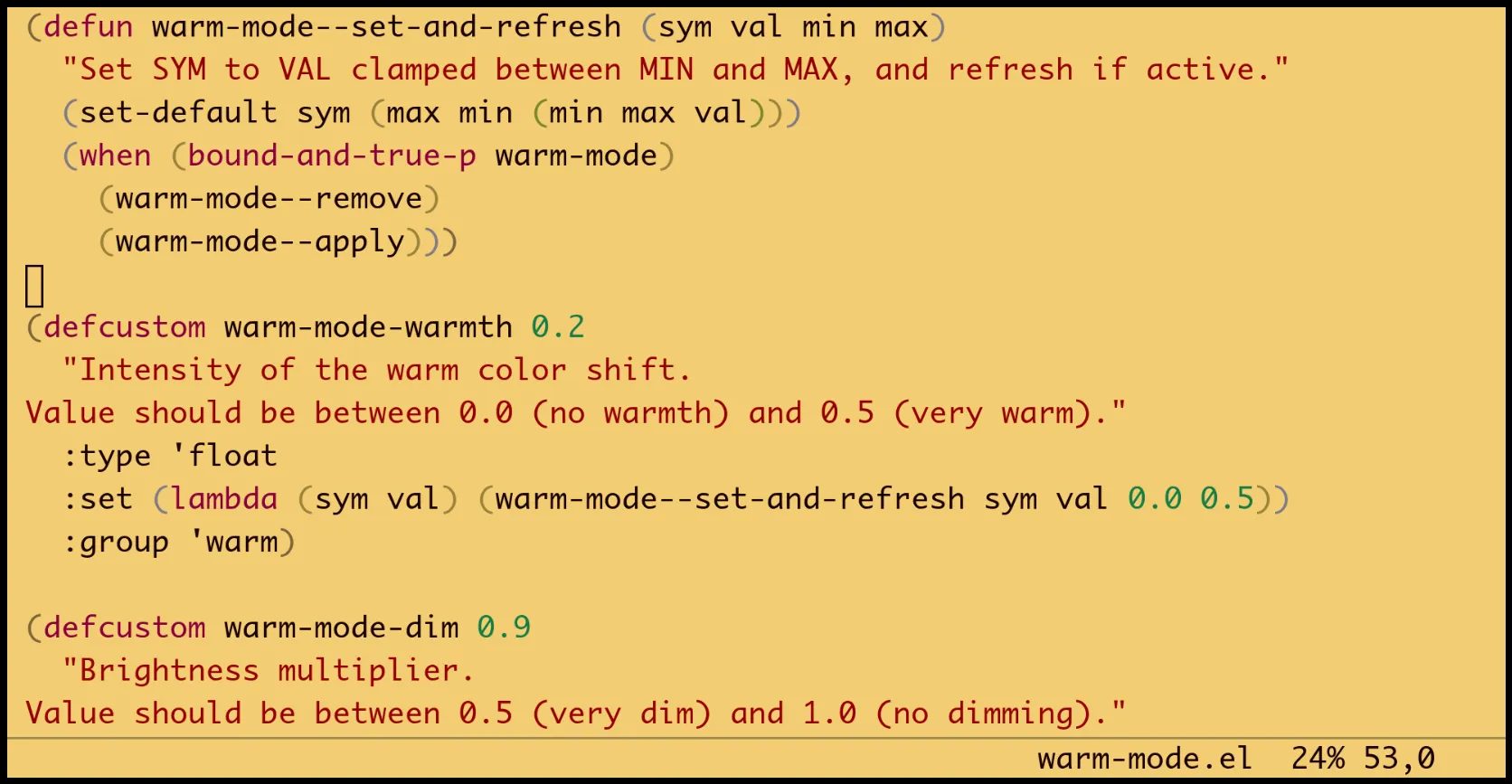

I use creamy, the same warm, minimal theme from my Doom setup. It strips away excess color and emphasizes only the essentials. For late-night sessions, warm-mode adds a subtle warm tint and dims colors. It is a package I wrote recently that shifts RGB values at runtime, reducing blue light and dimming brightness across all faces. It works with any theme without requiring theme-specific configuration:

(use-package warm-mode

:ensure (:host github :repo "smallwat3r/emacs-warm-mode")

:custom

(warm-mode-warmth 0.25)

(warm-mode-dim 0.9))Here is what it looks like, the creamy theme with warm-mode applied.

The font is Monaco (or MonacoB on Linux). It is the font I originally started programming with, and I keep coming back to it. Simple, compact, easy on the eye. Font setup is platform-aware and runs early to prevent frame flickering:

(defvar sw-font-family (if sw-is-mac "Monaco" "MonacoB"))

(defvar sw-font-size (if sw-is-mac 13 10))

(set-face-attribute 'default nil

:family sw-font-family

:height (* sw-font-size 10))

(push `(font . ,(format "%s-%d" sw-font-family sw-font-size))

default-frame-alist)b) The modeline, or lack of it

This is probably the most opinionated part of the config. The traditional mode-line is gone. Instead, buffer information lives in the echo area, right-aligned alongside any current message.

mini-modeline does something similar, but I wanted my own implementation. It is only a handful of lines, I understand every part of it, and it does exactly what I need with nothing extra:

(defun sw--update-echo-area ()

"Update echo area with buffer info."

(unless (active-minibuffer-window)

(let* ((info (format "%s%s %s %s,%d"

(if (buffer-modified-p) "** " "")

(buffer-name)

(format-mode-line "%p")

(format-mode-line "%l")

(current-column)))

(cur (or (current-message) ""))

(padding (- (frame-width)

(length cur) (length info) 1))

(msg (concat cur

(make-string (max 1 padding) ?\s)

info))

(message-log-max nil))

(message "%s" msg))))

(add-hook 'post-command-hook #'sw--update-echo-area)The display shows: modified marker (**), buffer name,

scroll position, line and column. Simple, always visible, and it

reclaims the entire mode-line area.

When there is only one window, the mode-line is hidden entirely. When multiple windows exist, it becomes a thin colored bar, red for active, dark gray for inactive, just enough to distinguish which window has focus:

(defun sw--update-mode-line-visibility ()

"Show mode-line only when frame has multiple windows."

(let ((fmt (if (> (count-windows) 1) " " nil)))

(dolist (win (window-list))

(with-selected-window win

(unless (eq mode-line-format fmt)

(setq mode-line-format fmt))))))

(set-face-attribute 'mode-line nil

:background "#e63946" :box nil :height 0.1)

(set-face-attribute 'mode-line-inactive nil

:background "#333333" :box nil :height 0.1)c) Dashboard

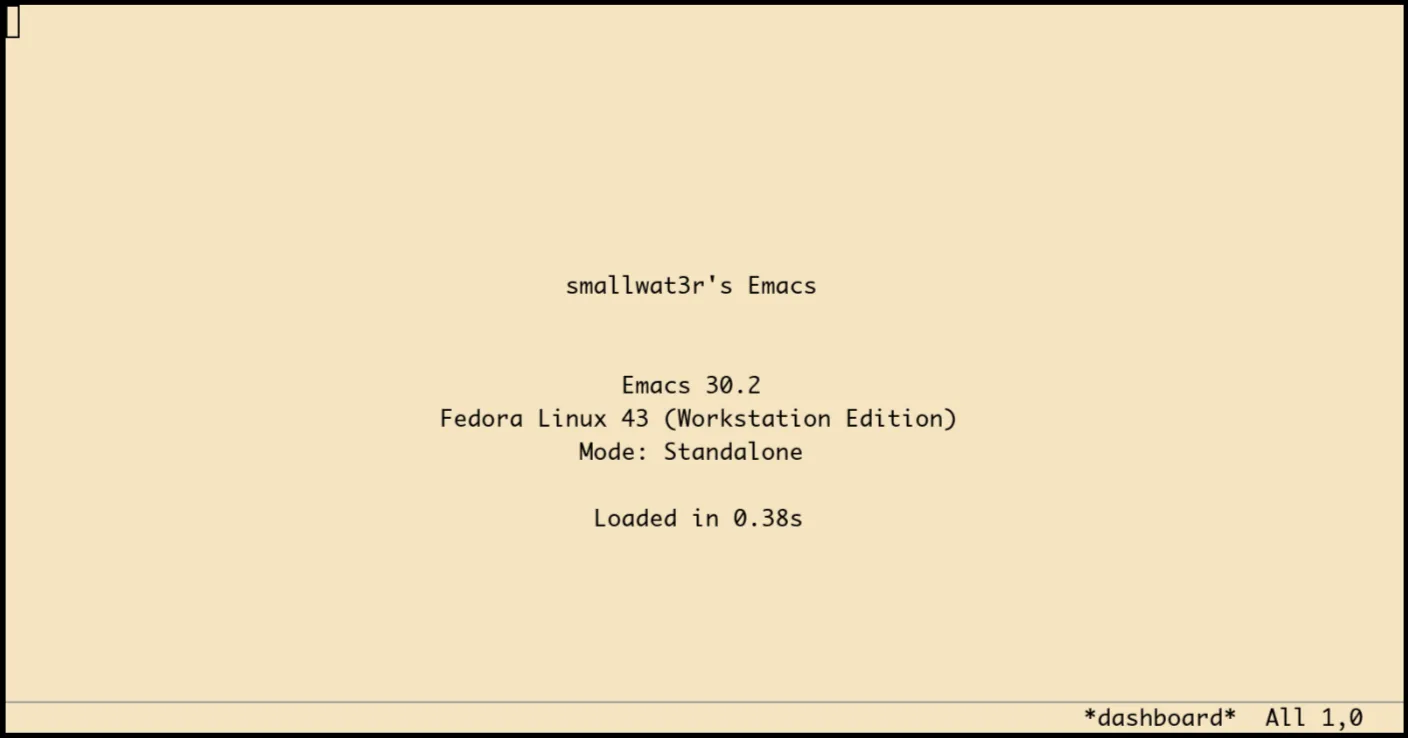

The dashboard is minimal, centered text showing the Emacs version, OS, mode (daemon or standalone), and load time. It re-renders on window resize to stay centered:

(defun sw-dashboard-render ()

"Render the dashboard content in the current buffer."

(with-silent-modifications

(erase-buffer)

(let* ((width (window-body-width))

(height (window-body-height))

(top-padding (max 0 (/ (- height 7) 2)))

(center (lambda (s)

(insert (make-string

(max 0 (/ (- width (length s)) 2))

?\s) s "\n")))

(load-time (float-time

(time-subtract after-init-time

before-init-time))))

(insert (make-string top-padding ?\n))

(funcall center "smallwat3r's Emacs")

(insert "\n\n")

(funcall center (format "Emacs %s" emacs-version))

(funcall center sw-dashboard--os-version)

(funcall center

(if (daemonp) "Mode: Daemon" "Mode: Standalone"))

(insert "\n")

(funcall center (format "Loaded in %.2fs" load-time)))))The buffer is protected from accidental kills and acts as a stable home base, similar to Doom’s dashboard but without the ASCII art or recent file list.

VI. Completion stack

The completion framework follows the modern Emacs approach: Vertico for the minibuffer, Corfu for in-buffer, Consult for enhanced search, and Orderless for flexible matching. This replaces Doom’s Vertico/Corfu modules with direct configuration.

(use-package vertico

:hook (sw-first-input . vertico-mode)

:custom

(vertico-count 10)

(vertico-resize nil)

(vertico-cycle t))

(use-package corfu

:hook (sw-first-input . global-corfu-mode)

:custom

(corfu-count 5)

(corfu-auto t)

(corfu-auto-delay 0.2)

(corfu-auto-prefix 2)

(corfu-cycle t)

(corfu-preselect 'prompt))

(use-package orderless

:custom

(completion-styles '(orderless basic))

:config

(setq orderless-matching-styles

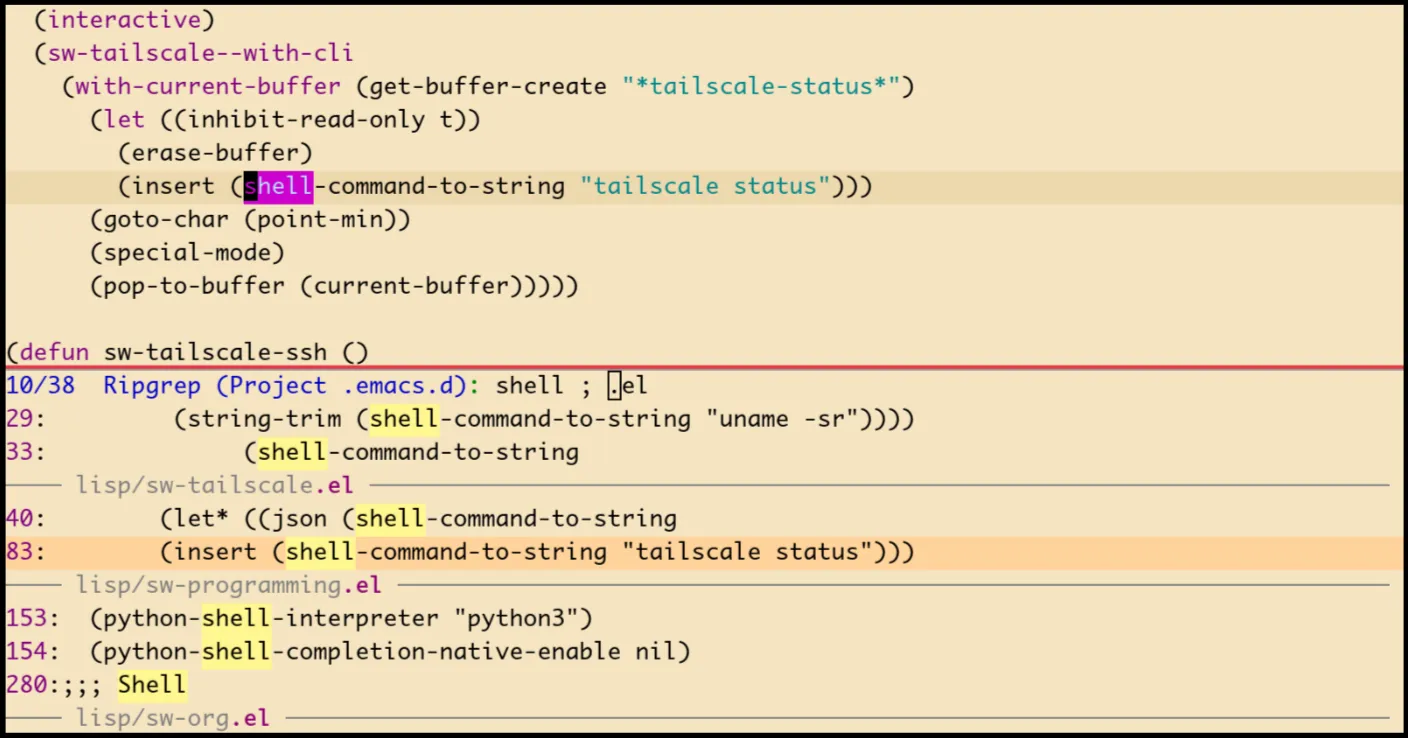

'(orderless-literal orderless-regexp orderless-flex)))Consult uses ripgrep and fd as backends, with async settings tuned for responsiveness:

(use-package consult

:custom

(consult-async-min-input 2)

(consult-async-refresh-delay 0.15)

(consult-async-input-throttle 0.2)

(consult-async-input-debounce 0.1)

:config

(setq consult-ripgrep-args

(concat "rg --null --line-buffered --color=never "

"--max-columns=1000 --path-separator / "

"--smart-case --no-heading --line-number "

"--hidden --glob !.git"))

(setq consult-fd-args

`(,(if (executable-find "fdfind") "fdfind" "fd")

"--color=never" "--hidden" "--exclude" ".git")))Cape

extends completion-at-point with dabbrev, file, and keyword sources. The

order matters, add-to-list pushes to the front, so the last

added runs first:

(use-package cape

:after corfu

:config

(add-to-list 'completion-at-point-functions #'cape-keyword)

(add-to-list 'completion-at-point-functions #'cape-file)

(add-to-list 'completion-at-point-functions #'cape-dabbrev))VII. Project management with project.el

Doom uses Projectile. It works well, but

project.el has been built into Emacs since version 28 and

integrates natively with xref, compilation buffers, and Consult. One

less dependency.

(use-package project

:ensure nil

:demand t

:custom

(project-list-file

(expand-file-name "projects" user-emacs-directory))

(project-switch-commands #'project-find-file)

:config

(setq project-vc-extra-root-markers

'(".project" ".projectile" "Cargo.toml" "go.mod"

"package.json" "pyproject.toml" "setup.py"

"Makefile" ".git")))Setting project-switch-commands to

#'project-find-file means switching projects goes directly

to the file finder instead of showing the project menu. One less

keypress.

Auto-discovery scans a few base directories on demand:

(defvar sw-project-directories

'("~/code" "~/work" "~/dotfiles"))

(defun sw-project-discover ()

"Scan `sw-project-directories' for git repos."

(interactive)

(dolist (dir sw-project-directories)

(let ((expanded (expand-file-name dir)))

(when (file-directory-p expanded)

(project-remember-projects-under expanded nil)))))Helper functions wrap Consult for project-scoped operations:

(defun sw-project-find-file ()

"Find file in current project using fd."

(interactive)

(consult-fd (sw-project-root-or-default)))

(defun sw-consult-ripgrep-project ()

"Search in current project with ripgrep."

(interactive)

(consult-ripgrep (sw-project-root-or-default)))VIII. Terminal with Eat

Doom offers multiple terminal options, but I stuck with vterm for its performance. It works well, but requires compiling a C library and has quirks with Evil mode. I switched to Eat, a pure Elisp terminal emulator that is easier to extend. Eat has its own quirks and is a little less fast than vterm, but being pure Elisp means no C library to compile and simpler integration with the rest of Emacs. Both support TRAMP.

a) Evil integration

The main challenge with any terminal in Evil mode is the state switching. In normal state, you want Emacs keybindings for scrolling and navigation. In insert state, keystrokes should go to the shell. Eat handles this with mode switching:

(defun sw-eat-evil-insert-enter ()

"Switch to semi-char mode when entering insert state."

(when (and (derived-mode-p 'eat-mode)

(not (eq eat--input-mode 'semi-char)))

(eat-semi-char-mode)))

(defun sw-eat-evil-insert-exit ()

"Switch to emacs mode when exiting insert state."

(when (and (derived-mode-p 'eat-mode)

(not (eq eat--input-mode 'emacs)))

(eat-emacs-mode)))

(add-hook 'evil-insert-state-entry-hook

#'sw-eat-evil-insert-enter)

(add-hook 'evil-insert-state-exit-hook

#'sw-eat-evil-insert-exit)Normal state gets Vim-style navigation, p to paste from kill ring, dd to send C-c, and RET to enter insert:

(evil-define-key* 'normal eat-mode-map

(kbd "B") #'beginning-of-line

(kbd "E") #'end-of-line

(kbd "G") #'end-of-buffer

(kbd "gg") #'beginning-of-buffer

(kbd "C-u") #'evil-scroll-up

(kbd "C-d") #'evil-scroll-down

(kbd "RET") #'evil-insert-state

(kbd "dd") #'sw-eat-interrupt

(kbd "p") #'sw-eat-yank)b) ZSH history integration

A custom command reads ~/.zsh_history and presents

completions inside Eat. If there is existing input on the command line,

it becomes a prefix filter via ^pattern:

(defun sw-eat-zsh-history-pick ()

"Prompt from zsh history and insert into eat.

Current input becomes a prefix filter (^pattern)."

(interactive)

(let* ((history (sw-zsh-history-candidates))

(input (sw-eat--current-input))

(choice (completing-read

"zsh history: " collection nil nil

(if input (concat "^" input) ""))))

(when input

(eat-term-send-string eat-terminal "\C-u"))

(eat-term-send-string eat-terminal choice)))Bound to C-, in both normal and insert states.

c) TRAMP integration

When opening an Eat buffer on a remote TRAMP connection, a hook

injects an e shell function that opens remote files in

local Emacs buffers. The approach is similar to what I had with vterm in

Doom, but adapted for Eat’s message handler protocol:

(defun sw-eat-setup-tramp (proc)

"Configure eat for TRAMP: rename buffer, inject `e` opener."

(when-let* ((buf (process-buffer proc))

(_ (file-remote-p default-directory))

(tramp-prefix (file-remote-p default-directory)))

(with-current-buffer buf

(rename-buffer (format "*eat@%s*" tramp-prefix) t)

;; Poll for prompt readiness, then send initialization

(let ((timer nil) (attempts 0))

(setq timer

(run-with-timer 0.1 0.1

(lambda ()

(setq attempts (1+ attempts))

(if (or sw-eat-tramp-initialized

(>= attempts 20)

(not (process-live-p proc)))

(cancel-timer timer)

(sw-eat--try-send-tramp-init

proc tramp-prefix)))))))))The initialization polls every 100ms, looking for a shell prompt

before sending the e function definition. This avoids the

race condition where the shell is not ready to receive input yet, a

problem that plagued the vterm approach.

Once the prompt is detected, it sends a shell function definition

over the wire. The injected e function resolves relative

paths, checks the file exists, then emits an OSC 51 escape sequence that

Eat intercepts. The payload is base64-encoded and tells Emacs to run

find-file with the full remote path. Simplified, the shell

function looks like:

e() {

local f="$1"

[[ "$f" != /* ]] && f="$PWD/$f"

printf '\033]51;e;M;%s;%s\033\\' \

"$(printf 'find-file' | base64)" \

"$(printf '%s' "$f" | base64)"

}The actual Elisp function that generates and sends this (with proper escaping and error handling) is:

(defun sw-eat--tramp-init-string (prefix)

"Return shell initialization string for TRAMP with PREFIX."

(format "export TERM=xterm-256color

e() { [ -z \"$1\" ] && { echo 'usage: e FILE' >&2; return 1; }; \

local f=\"$1\"; [[ \"$f\" != /* ]] && f=\"$PWD/$f\"; \

[ ! -e \"$f\" ] && { echo \"e: $f: no such file\" >&2; return 1; }; \

printf '\\033]51;e;M;%%s;%%s\\033\\\\' \

\"$(printf 'find-file' | base64)\" \

\"$(printf '%s%%s' \"$f\" | base64)\"; }

clear\n" prefix))On the Emacs side, a message handler receives the

find-file command and opens the file in another window:

(defun sw-eat-find-file-handler (path)

"Open PATH in another window."

(when (and path (not (string-empty-p path)))

(find-file-other-window path)))

(add-to-list 'eat-message-handler-alist

'("find-file" . sw-eat-find-file-handler))From a remote shell, e .bashrc opens

/ssh:user@host:.bashrc in a local Emacs buffer.

IX. Workspaces with tab-bar

Doom uses persp-mode for workspaces. It is powerful but heavy, and its interaction with Evil and buffer management was a constant source of subtle bugs.

I replaced it with built-in tab-bar-mode, extended with

buffer tracking per workspace. The tab bar itself is hidden

(tab-bar-show nil), workspaces are managed entirely through

keybindings and the echo area:

(defun sw-workspace--format-tab (index name is-current)

"Format a single tab for echo area display."

(let* ((num (1+ index))

(label (if (and name (not (string-empty-p name)))

(format "[%d] %s" num name)

(number-to-string num)))

(text (if is-current

(format "(%s) " label)

(format " %s " label)))

(face (if is-current

'sw-workspace-tab-selected-face

'sw-workspace-tab-face)))

(propertize text 'face face)))Pressing SPC TAB TAB (same binding as Doom) shows the workspace bar in the echo area.

Every workspace

operation (create, switch, close) also triggers a display update via

advice on tab-bar functions.

Every workspace

operation (create, switch, close) also triggers a display update via

advice on tab-bar functions.

a) Project workspaces

SPC p p (also same as Doom) switches to a project, creating a dedicated workspace for it. If a workspace for that project already exists, it switches to it instead:

(defun sw-workspace-switch-to-project ()

"Switch project, opening it in a dedicated workspace."

(interactive)

(let* ((dir (project-prompt-project-dir))

(name (file-name-nondirectory

(directory-file-name dir)))

(existing (member name (sw-workspace--get-names))))

(if existing

(tab-bar-switch-to-tab name)

(let ((tab-bar-new-tab-choice #'sw-fallback-buffer))

(tab-bar-new-tab)

(tab-bar-rename-tab name)

(delete-other-windows)

;; ...

))))b) Buffer tracking

Each workspace tracks which buffers belong to it. When a workspace is closed, its buffers are killed automatically:

(defvar sw-workspace-buffer-alist nil

"Alist mapping workspace names to their buffer lists.")

(defun sw-workspace--track-buffer (&rest _)

"Track current buffer in workspace buffer list."

(when-let ((buf (current-buffer)))

(unless (minibufferp buf)

(sw-workspace--add-buffer buf))))

(add-hook 'window-buffer-change-functions

#'sw-workspace--track-buffer)This replicates the most useful part of persp-mode, isolated buffer

lists per workspace, without the complexity. The fallback buffer

(*scratch*) is always preserved.

c) Quick switching

A macro generates numbered switching functions, so SPC TAB 1 through SPC TAB 9 jump directly to a workspace:

(defmacro sw-workspace--define-switchers ()

"Define workspace switching functions 1-9."

`(progn

,@(mapcar

(lambda (n)

`(defun ,(intern (format "sw-workspace-switch-to-%d" n)) ()

,(format "Switch to workspace %d." n)

(interactive)

(if (<= ,n (length (tab-bar-tabs)))

(tab-bar-select-tab ,n)

(message "Workspace %d does not exist" ,n))))

(number-sequence 1 9))))X. Keybindings and Evil

The Evil setup follows the same pattern as Doom: SPC as leader, which-key for discoverability (built into Emacs since version 30). I used Doom for so long that its keybinding conventions are burned into my muscle memory, and they were great to begin with, so I kept them.

a) Leader key

I dropped general.el since I was only using a fraction of

what it offers - mostly general-create-definer and

general-define-key, both easily replaced by a plain keymap

and evil-define-key*.

A global minor mode owns the leader keymap.

evil-define-key* binds SPC to it in normal,

visual and motion states, with C-SPC as global fallback:

(defvar sw-leader-map (make-sparse-keymap)

"Keymap for SPC leader bindings.")

(define-minor-mode sw-leader-mode

"Global minor mode providing SPC as leader key."

:global t :lighter nil

:keymap (make-sparse-keymap))

(sw-leader-mode 1)

(evil-define-key* '(normal visual motion)

sw-leader-mode-map

(kbd "SPC") sw-leader-map)

(global-set-key (kbd "C-SPC") sw-leader-map)A small helper, sw-define-keys, wraps

define-key and registers which-key labels in one pass. Each

entry is a (KEY DEF LABEL) triple, where a nil

DEF marks a prefix-only group:

(defun sw-define-keys (keymap bindings)

"Define BINDINGS in KEYMAP with which-key labels.

BINDINGS is a list of (KEY DEF LABEL) entries.

DEF is a command or nil (prefix-only label)."

(let (wk-args)

(dolist (b bindings)

(pcase-let ((`(,key ,def ,label) b))

(when def

(define-key keymap (kbd key) def))

(when label

(push key wk-args)

(push label wk-args))))

(when wk-args

(apply #'which-key-add-keymap-based-replacements

keymap (nreverse wk-args)))))This keeps all bindings declarative and compact. For example, the buffer group looks like:

(sw-define-keys sw-leader-map

'(("b" nil "Buffer")

("b b" sw-workspace-switch-buffer "Switch buffer")

("b d" kill-current-buffer "Kill buffer")

("b s" save-buffer "Save buffer")

...))The major prefix groups mirror Doom’s layout closely, SPC

b for buffers, SPC f for files, SPC g for

git, SPC s for search, SPC p for projects,

SPC w for windows. SPC m dispatches to

mode-specific bindings, just like Doom’s local leader. A

menu-item filter looks up the current major mode in an

alist and returns the matching keymap:

(defvar sw-local-leader-alist nil

"Alist of (MODE . KEYMAP) for SPC m bindings.")

(define-key sw-leader-map "m"

`(menu-item "Local mode" nil

:filter ,(lambda (&optional _)

(sw-local-leader-keymap))))Each mode registers its own keymap. For instance, Python gets test runners and import sorting under SPC m, while Emacs Lisp gets eval commands.

c) Symbol highlighting

Evil’s default * searches for the word at point but jumps to the next match. This custom version highlights the symbol at point without moving the cursor. Press n/N to jump between matches, Escape to clear:

(defun sw-highlight-symbol-at-point ()

"Highlight symbol at point without moving."

(interactive)

(let* ((symbol (or (thing-at-point 'symbol t)

(user-error "No symbol at point")))

(pattern (format "\\_<%s\\_>"

(regexp-quote symbol))))

(setq evil-ex-search-pattern

(evil-ex-make-search-pattern pattern)

evil-ex-search-direction 'forward)

(evil-push-search-history pattern t)

(evil-ex-delete-hl 'evil-ex-search)

(evil-ex-make-hl 'evil-ex-search)

(evil-ex-hl-change 'evil-ex-search

evil-ex-search-pattern)

(evil-ex-hl-update-highlights)))XI. Programming and formatting

a) Tree-sitter everywhere

Emacs 29+ has built-in tree-sitter support. A single remap table switches all major modes to their tree-sitter variants:

(setq major-mode-remap-alist

'((c-mode . c-ts-mode)

(python-mode . python-ts-mode)

(go-mode . go-ts-mode)

(rust-mode . rust-ts-mode)

(js-mode . js-ts-mode)

(json-mode . json-ts-mode)

(sh-mode . bash-ts-mode)

(yaml-mode . yaml-ts-mode)

;; ...

))b) Region formatting with dedenting

Apheleia handles whole-buffer formatting on save, but it does not support formatting a region. This custom region formatter fills that gap, and also handles indented code correctly. This comes up when formatting code inside Python docstrings or nested blocks, where the selection has leading indentation that confuses formatters:

(defun sw-format-region ()

"Format the current region using language-specific tools."

(interactive)

(let* ((beg (region-beginning))

(end (region-end))

(formatter (alist-get major-mode sw-region-formatters))

(input (buffer-substring-no-properties beg end))

(indent (sw--string-min-indent input))

(dedented (sw--string-reindent input indent 0)))

;; Format the dedented code, then reindent

;; ...

(insert (sw--string-reindent output 0 indent))))The formatter strips leading indentation, pipes through the external tool (black, gofmt, shfmt, etc.), then reindents the result. Bound to ;f in visual state.

c) Eglot with booster

Eglot runs with minimal settings, async connection, no event buffer, and no inlay hints:

(use-package eglot

:custom

(eglot-autoshutdown t)

(eglot-events-buffer-size 0)

(eglot-sync-connect nil)

(eglot-connect-timeout 10)

(eglot-ignored-server-capabilities '(:inlayHintProvider)))Eglot-booster wraps LSP communication through emacs-lsp-booster, a Rust binary that handles IO buffering:

(use-package eglot-booster

:ensure (:host github :repo "jdtsmith/eglot-booster")

:after eglot

:when (executable-find "emacs-lsp-booster")

:init

(setq eglot-booster-io-only (> emacs-major-version 29)))The io-only flag disables bytecode pre-compilation of

JSON messages and relies on Emacs’ native JSON parser instead. Emacs 30

introduced a substantially faster JSON decoder, making bytecode

translation unnecessary. The IO buffering benefits are still active

either way.

XII. Backward kill word

A small but frequently useful enhancement. The default

backward-kill-word is too aggressive, deleting entire

compound identifiers in one shot. This version stops at underscores,

hyphens, and other word boundaries:

(defun sw-backward-kill-word ()

"Kill backward more gradually than `backward-kill-word'.

Stops at word boundaries including underscores and hyphens."

(interactive)

(let* ((start (point))

(end (save-excursion

(cond

((bobp) (point))

((looking-back "[ \t\n]" (1- (point)))

(skip-chars-backward " \t\n")

(when (= (- start (point)) 1)

(when (looking-back

"[^[:alnum:][:space:]]" (1- (point)))

(skip-chars-backward "^[:alnum:][:space:]"))

(when (looking-back

"[[:alnum:]]" (1- (point)))

(skip-chars-backward "[:alnum:]")))

(point))

((looking-back "[_-]+" (line-beginning-position))

(skip-chars-backward "_-")

(when (looking-back

"[[:alnum:]]" (1- (point)))

(skip-chars-backward "[:alnum:]"))

(point))

(t

(skip-chars-backward "[:alnum:]")

(point))))))

(kill-region end start)))Bound to C-Backspace globally. With the cursor at the end

of my_long_variable_name, the default kills the whole

thing. This version stops at each boundary:

my_variable_name->my_variable_->my_variable->my_-> …some-kebab-case->some-kebab-->some--> …foo(bar, baz)->foo(bar,->foo(-> …hello world->hello-> …

~~~

Wrapping up

This configuration keeps evolving with my workflow, and that is the point. Unlike Doom, where the framework owned most of the behavior and I was patching around the edges, everything here is mine. When something breaks, the fix lives in my code, not in a module interaction I never fully understood.

The core philosophy is simple: use built-in features where they are good enough (project.el, tab-bar, eglot, tree-sitter), add carefully chosen packages where they are not (Vertico, Corfu, Magit, Evil), and write custom glue only where no existing solution fits. Keep the UI minimal, the startup fast, and the code readable.

If you are considering a similar move, my advice is: do not try to replicate your current setup. Start with a blank file, add things as you actually miss them, and resist the urge to port everything at once. You will be surprised how little you actually need.

Links

- My Emacs config (5570fb3), the full vanilla Emacs configuration

- Doom Emacs config, the previous setup this replaces

- Elpaca, the package manager

- Creamy theme, the warm, paper-like theme

- Warm mode, night-time color warmth