Making ZSH fast

Introduction

In a previous post, I walked through my modular ZSH configuration, covering the structure, hacks, prompt, and tool integrations. There will be some crossover with that article, though a few things have changed and been improved since. I have been chasing startup time, trying to get as close to instant as possible without giving up features.

The goal: a shell that starts in under 30ms, with git status in the prompt, syntax highlighting, completions, and configs for a dozen tools. No framework, no plugin manager, no daemon processes.

My philosophy is to only use what I need, and when possible, write it myself rather than pulling in plugins. This is not advice that everyone should do the same, but I like being in full control of what happens in my shell.

This post covers the tips and tricks that got me there, with profiling data and benchmarks.

I. Why it matters

Shell startup time compounds. You open terminals constantly, split tmux panes, run

zsh -c in scripts, spawn subshells from editors. A 200ms

startup is barely noticeable once, but it becomes friction when it

happens dozens of times a day.

Most of the overhead comes from loading things you don’t need yet, or loading them in expensive ways.

II. Measuring

You can not optimize what you can not measure. ZSH ships with two useful tools for this.

a)

time and timezsh

The simplest benchmark is time:

$ time zsh -i -c exit

zsh -i -c exit 0.01s user 0.02s system 96% cpu 0.029 total

This starts an interactive shell (-i), runs

exit, and reports the wall-clock time. On my machine, a

bare zsh --no-rcs takes 4ms. My full config takes about

29ms here (0.029 total). Averaged over multiple runs, it settles around

24ms.

For more consistent results, I use a timezsh function

that averages multiple runs:

# ~/.zsh/functions/timezsh (autoloaded)

zmodload zsh/datetime

runs=${1:-10}

total_ms=0

for i in {1..$runs}; do

start=$EPOCHREALTIME

zsh -i -c exit >/dev/null 2>&1

end=$EPOCHREALTIME

delta_ms=$(( (end - start) * 1000 ))

total_ms=$(( total_ms + delta_ms ))

printf "run %2d: %3.0f ms\n" "$i" "$delta_ms"

done

printf "\nAverage: %.0f ms\n" "$(( total_ms / runs ))"Each iteration spawns a fresh interactive ZSH process

(zsh -i), which sources .zshrc and the full

config chain, then immediately exits (-c exit).

$EPOCHREALTIME from the zsh/datetime module

captures wall-clock time before and after each fork, so the delta is the

real startup cost: process creation, config sourcing, and teardown.

Running it with 10 iterations:

$ timezsh 10

run 1: 27 ms

run 2: 25 ms

run 3: 27 ms

run 4: 26 ms

run 5: 23 ms

run 6: 22 ms

run 7: 23 ms

run 8: 23 ms

run 9: 24 ms

run 10: 23 ms

Average: 24 ms

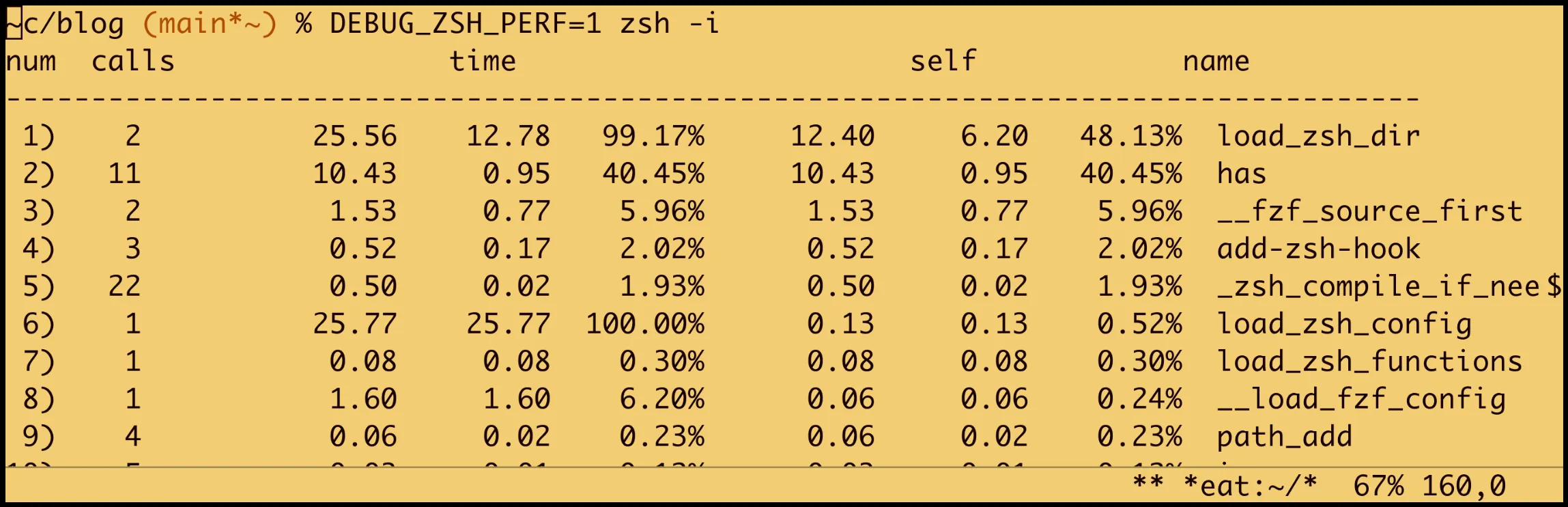

b) zprof

For a detailed breakdown, ZSH’s built-in profiler shows where time is spent:

# top of .zshrc

if (( ${+DEBUG_ZSH_PERF} )); then

zmodload zsh/zprof

fi

# ... config loads ...

# bottom of .zshrc

if (( ${+DEBUG_ZSH_PERF} )); then

zprof

fiRun it with DEBUG_ZSH_PERF=1 zsh -i to get a

function-level profile (shortened here):

num calls time self name

-------------------------------------------------

1) 11 9.95ms 9.95ms has

2) 2 21.84ms 9.42ms load_zsh_dir

3) 2 1.39ms 1.39ms __fzf_source_first

4) 22 0.46ms 0.46ms _zsh_compile_if_needed

5) 3 0.45ms 0.45ms add-zsh-hook

# ...

The profile reveals what is actually slow. In my case, the

has checks (11 calls to test if commands exist) take about

10ms total, and loading tool directories takes most of the remaining

time. Bytecode compilation checks are cheap at 0.46ms for 22 files.

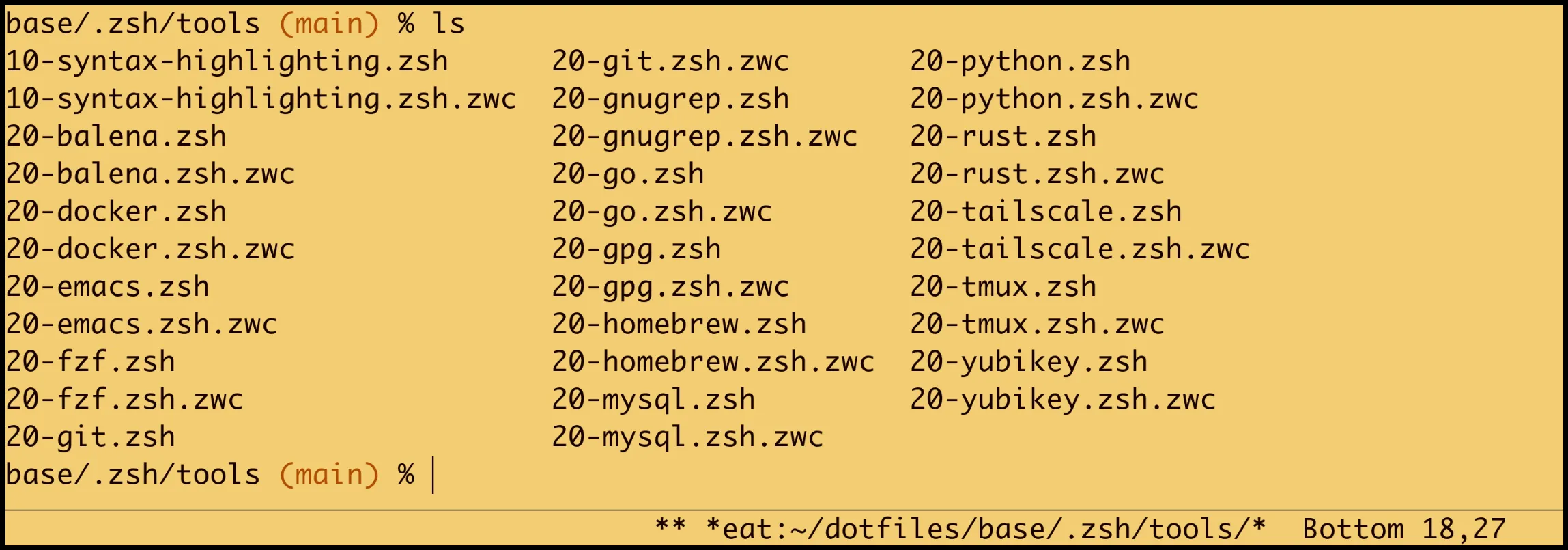

III. Bytecode compilation

ZSH can compile scripts to a bytecode format (.zwc

files), similar to Python’s .pyc. The compiled version is

loaded automatically when present and newer than the source.

_zsh_compile_if_needed() {

local src=$1 dst="${1}.zwc"

[[ -n $src && -r $src ]] || return 1

if [[ ! -f $dst || $src -nt $dst ]]; then

zcompile "$src" 2>/dev/null

fi

}This is called before sourcing each config file:

load_zsh_dir() {

local dir=$1 file

[[ -d $dir && -r $dir ]] || return 0

for file in "$dir"/*.zsh(N); do

[[ -r $file ]] || continue

_zsh_compile_if_needed "$file"

source "$file"

done

}The first shell startup after editing a file compiles it. Every subsequent startup uses the cached bytecode. The check itself is nearly free, just a file stat comparison.

Compilation also applies to the completion dump file

(.zcompdump), which is one of the more expensive files to

parse.

IV. Deferred initialization

The single biggest optimization is deferring work that does not need

to happen before the first prompt appears. ZSH’s precmd

hook runs just before each prompt is drawn. By scheduling initialization

there, the shell becomes interactive immediately, and the setup finishes

in the background of the first prompt render.

a) Completion system

compinit is expensive. It scans fpath

directories, reads completion functions, and builds an internal lookup

table. On a clean run, this takes 30-60ms. With caching (-C

flag), it drops to a few milliseconds, but even that is wasted if you

don’t need completion before the first prompt. The gain is modest on its

own, 24ms deferred vs 34ms synchronous, but when chasing startup time

every millisecond counts.

autoload -Uz compinit

__deferred_compinit() {

local dump_dir=${XDG_CACHE_HOME:-$HOME/.cache}/zsh

local dump=$dump_dir/.zcompdump

mkdir -p "$dump_dir" 2>/dev/null

if [[ ! -f $dump ]]; then

compinit -d "$dump"

else

compinit -C -d "$dump" # -C skips security check

fi

_zsh_compile_if_needed "$dump"

# wire up alias-expansion now that compinit has run

zle -C alias-expansion complete-word _generic

bindkey '^a' alias-expansion

add-zsh-hook -d precmd __deferred_compinit

unfunction __deferred_compinit

}

autoload -Uz add-zsh-hook

add-zsh-hook precmd __deferred_compinitThe pattern is consistent: register a precmd hook, do

the work, unhook and delete the function. The hook only runs once.

The -C flag tells compinit to skip the security check

that verifies file ownership and permissions on completion files. This

check is redundant on a single-user machine and saves a noticeable

amount of time.

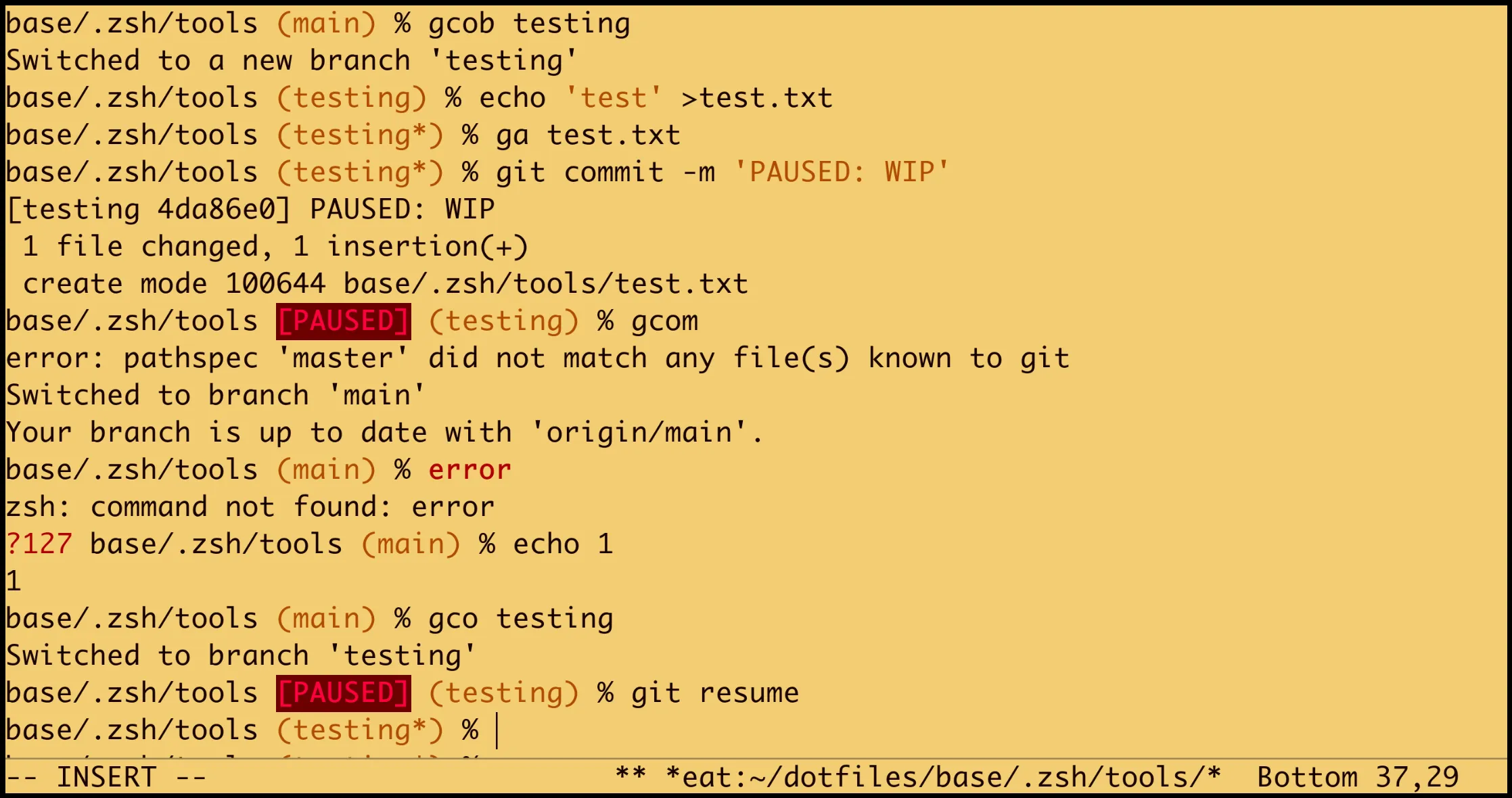

b) Git alias generation

My config auto-generates g<alias> shell aliases

from git’s own alias configuration (e.g., gco for

git checkout). This requires forking

git config, which adds a few milliseconds to startup (28ms

vs 24ms). Small, but free to defer:

__load_git_aliases() {

local line key name

local git_alias_lines

git_alias_lines=(

"${(@f)$(git config --get-regexp '^alias\.' 2>/dev/null)}"

)

for line in $git_alias_lines; do

key=${line%% *} # "alias.co"

name=${key#alias.} # "co"

alias "g${name}=git ${name}"

done

alias g="git"

add-zsh-hook -d precmd __load_git_aliases

unfunction __load_git_aliases

}

autoload -Uz add-zsh-hook

add-zsh-hook precmd __load_git_aliasesBy deferring this to the first prompt, the git config

fork happens after the shell is already interactive. You never notice

the delay.

c) The self-cleaning hook pattern

Both examples above follow the same pattern:

__deferred_work() {

# ... do expensive thing ...

add-zsh-hook -d precmd __deferred_work

unfunction __deferred_work

}

add-zsh-hook precmd __deferred_workRegister a precmd hook, do the work on first prompt,

then unhook and clean up. No ongoing cost after initialization, and the

function is removed from memory.

V. The prompt

The prompt is the most latency-sensitive part of the config, it runs before every single command. A slow prompt makes the entire shell feel sluggish.

a) Avoiding subshell forks

A common approach is to use command substitution in the prompt string:

# slow: forks a subshell on every prompt

PROMPT='$(__git_status) %# 'Every $(...) in the prompt string forks a subshell. Even

a fast function adds measurable overhead when it forks on every

keypress.

What I do instead is compute everything in a precmd hook

and store results in variables:

__prompt_precmd() {

local last_status=$?

__ps_err='' __ps_tag='' __ps_venv='' __ps_git=''

# exit status

(( last_status )) && __ps_err="%F{red}?${last_status} "

# session tag

[[ -n $_PROMPT_TAG ]] && \

__ps_tag="%B%F{87}%K{20}[${(U)_PROMPT_TAG}]%b%f%k "

# virtualenv

(( ${+VIRTUAL_ENV} )) && \

__ps_venv="venv(${VIRTUAL_ENV##*/}) "

# git (details in next section)

# ...

}

add-zsh-hook precmd __prompt_precmd

PROMPT='${__ps_err}${__ps_tag}${__ps_venv}'

PROMPT+='%f%3~%f${__ps_git}%# 'The prompt string now just references variables, no subshells. The

precmd hook does the same work, but runs in the current

shell process instead of forking a child for each $(...).

The cost is the same computation, without the overhead of process

creation on every prompt render.

b) Fast git status

The git segment is the most expensive part of the prompt. It needs to check branch name, dirty state, and a custom PAUSED badge. Here is how I made it fast, keeping everything internal with no plugins or external tools:

# inside __prompt_precmd

local gstatus branch dirty root paused

gstatus=$(

GIT_OPTIONAL_LOCKS=0 \

git status --porcelain=v2 -b \

--no-ahead-behind 2>/dev/null

) || return

branch=${gstatus#*branch.head }

branch=${branch%%$'\n'*}

[[ -z $branch || $branch == "# "* ]] && return

[[ $gstatus == *$'\n'[^#]* ]] && dirty='*'

[[ -e .git ]] && root='~'Three things make this fast:

GIT_OPTIONAL_LOCKS=0

tells git not to acquire the optional repository lock. In a prompt

context, you only read state, you never write it. Skipping locks avoids

contention on busy repositories where other git processes might hold the

lock. Since it’s set inside the $(...) subshell, it doesn’t

persist in your normal shell session.

--no-ahead-behind

skips counting commits ahead and behind the remote. This avoids

network-related delays and an extra traversal of the commit graph. If

you don’t display ahead/behind counts in your prompt, there is no reason

to compute them.

--porcelain=v2 gives a

machine-stable output format that includes branch metadata in header

lines (prefixed with #). Dirty files appear as non-header

lines, so checking for dirtiness is a single pattern match rather than

counting output lines:

# branch.oid bf82688de9aaa75acf3c6400a3295d966204fdde

# branch.head main

# branch.upstream origin/main

? content/blog/fast-zsh.dj

? static/images/fast-zsh/

c) OID caching for commit subject

My prompt shows a PAUSED badge when the last commit message starts

with “PAUSED”. This requires reading the commit subject, normally a

git log fork. But the OID (object ID) is the SHA of the

HEAD commit, and a commit’s subject is immutable, so a given OID always

maps to the same message. HEAD only changes on commits, checkouts, or

rebases, not between normal prompt renders. Caching by OID avoids

redundant forks:

local oid=${gstatus#*branch.oid }

oid=${oid%%$'\n'*}

if [[ $oid != "${__git_prev_oid-}" ]]; then

__git_prev_oid=$oid

__git_prev_subject=$(

git log -1 --format=%s 2>/dev/null

)

fi

[[ $__git_prev_subject == PAUSED* ]] && \

paused=' %B%F{198}%K{52}[PAUSED]%b%f%k'The porcelain=v2 output already includes

branch.oid, so extracting it is free. When HEAD hasn’t

changed (which is most prompts), the cached subject is reused and no

git log fork happens. This effectively reduces the prompt

to a single git command in the common case.

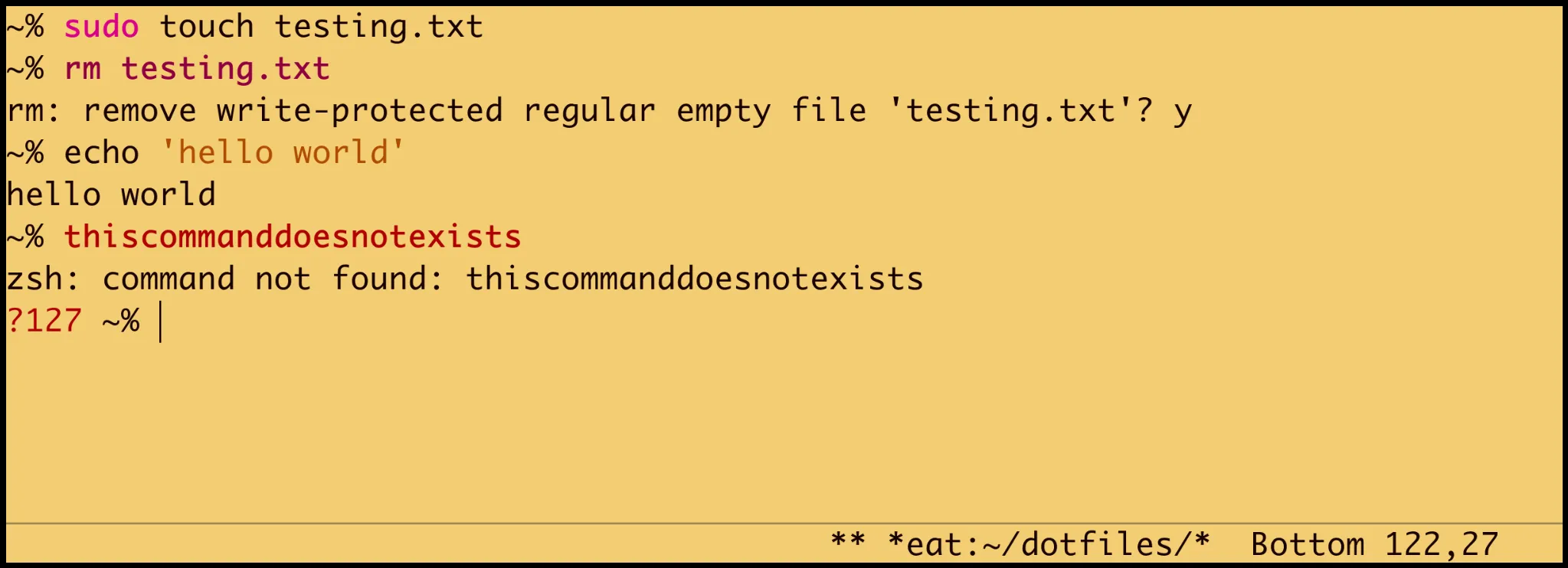

VI. Replacing external plugins

I used zsh-syntax-highlighting for years, and it’s very good. But it does far more than I need or use, with full syntax analysis, dozens of token types, and path validation. For my use case, a fraction of its functionality is enough. You can hook in lots of colors and rules, but I like to keep things minimal.

I replaced it with ~60 lines of custom highlighting using ZSH’s

built-in region_highlight mechanism:

__syntax_hl() {

emulate -L zsh

# skip if buffer unchanged (redraws without edits)

[[ $BUFFER == "${__syntax_hl_prev-}" ]] && return

__syntax_hl_prev=$BUFFER

region_highlight=()

(( $#BUFFER )) || return

# first word (skip leading whitespace and VAR=val prefixes)

local cmd=${BUFFER##[[:space:]]#}

local -i offset=$(( $#BUFFER - $#cmd ))

cmd=${cmd%%[[:space:]]*}

[[ -n $cmd ]] || return

while [[ $cmd == *=* ]]; do

local rest=${BUFFER:$(( offset + $#cmd ))}

rest=${rest##[[:space:]]#}

offset=$(( $#BUFFER - $#rest ))

cmd=${rest%%[[:space:]]*}

[[ -n $cmd ]] || return

done

local -i cmd_end=$(( offset + $#cmd ))

# rm: dim bold on the whole line

if [[ $cmd == rm ]]; then

region_highlight+=("0 $#BUFFER fg=90,bold")

return

fi

# sudo: purple bold

if [[ $cmd == sudo ]]; then

region_highlight+=("$offset $cmd_end fg=164,bold")

return

fi

# unknown command: red bold

if ! whence -- "$cmd" >/dev/null 2>&1; then

region_highlight+=("$offset $cmd_end fg=red,bold")

fi

# quoted strings

local QS="'" QD='"'

local -i pos=1 sq dq next close

while (( pos <= $#BUFFER )); do

sq=${BUFFER[(ib:pos:)$QS]}

dq=${BUFFER[(ib:pos:)$QD]}

if (( sq < dq )); then

next=$sq

close=${BUFFER[(ib:next+1:)$QS]}

elif (( dq <= $#BUFFER )); then

next=$dq

close=${BUFFER[(ib:next+1:)$QD]}

else

break

fi

if (( close <= $#BUFFER )); then

region_highlight+=(

"$(( next - 1 )) $close fg=yellow"

)

pos=$(( close + 1 ))

else

break

fi

done

}

zle -N zle-line-pre-redraw __syntax_hlThis highlights four things: unknown commands (red), rm

(dim bold as a visual warning), sudo (purple), and quoted

strings (yellow). That covers the patterns I actually care about.

The buffer caching (__syntax_hl_prev) is key. The

zle-line-pre-redraw hook fires on every redraw, including

cursor movement and window resizes. Without the cache check, the

highlighting logic would run on every keystroke even when nothing

changed.

The result: no external dependencies, no plugin manager, no slow

initialization, and highlighting that covers the dangerous patterns

(rm, sudo), unknown commands, and quoted

strings as nice visual indicators.

VII. Conditional loading

Every tool config checks if the tool exists before doing anything:

has git || return

has docker || return

has fzf || returnThe has function uses ZSH’s $commands

associative array, which is a hash lookup, not a which or

command -v fork:

has() {

local cmd

for cmd in "$@"; do

(( $+commands[$cmd] )) || return 1

done

}This has two benefits. On machines where a tool isn’t installed, there is zero cost, the file returns immediately. And it avoids errors from trying to configure nonexistent commands.

With 16 tool config files, this adds up. On a minimal server with only git installed, most tool configs bail out in microseconds.

VIII. Autoloaded functions

Functions in ~/.zsh/functions/ are registered with

fpath and autoload, not sourced:

load_zsh_functions() {

local fn_dir=${1}/functions

[[ -d $fn_dir ]] || return 0

fpath=("$fn_dir" $fpath)

autoload -U "$fn_dir"/*(:tN)

}ZSH’s autoload mechanism only records the function name at startup.

The function body is read from disk on first call. For functions like

timezsh, cr (jump to git root), or

take (mkdir and cd), this means zero startup cost. The

function loads when you actually use it.

IX. What to avoid

Some things that seem like they should help but don’t, or that actively hurt:

Plugin managers. Don’t get me wrong, tools like Oh My Zsh, Prezto, or zinit are really good and helpful, specially if you want something nice and pretty that works out of the box. But they add their own initialization overhead. If you’re loading a handful of features, writing them yourself could often be faster, as you only use what you actually need, and gives you complete control over when things load.

Prompt daemons. Tools like gitstatus run a background process for git

information. Very effective for large monorepos, but overkill for most

normal-sized repositories and adds complexity. A single

git status --porcelain=v2 with the right flags is most of

the time fast enough, and avoids another external dependency and a

running daemon.

Lazy eval wrappers. A

common pattern is wrapping tool init (e.g. pyenv) in a

function that replaces itself on first call:

# avoid this

pyenv() {

unfunction pyenv

eval "$(pyenv init -)"

pyenv "$@"

}This saves startup time but the first invocation takes the hit

instead, and completions won’t be available until you’ve called the

command once. Deferring to precmd avoids both issues, since

everything is ready before you type your first command.

Excessive history sizes without

limits. A large HISTSIZE is fine

(HISTSIZE=1000000), but ZSH loads the entire history into

memory on startup. At around 30 bytes per entry, a million records would

be roughly 30MB. Unlikely to cause issues on modern machines, but worth

keeping an eye on if your history grows unchecked.

X. Results

The final numbers on my machine (Fedora, Ryzen 7, NVMe):

Bare ZSH (--no-rcs): 4 ms

Full config: 24 ms

Overhead: 20 ms

That 20ms buys: modular config loading with bytecode compilation, completion system with caching, git status in prompt with OID caching, custom syntax highlighting, FZF with ripgrep, and configs for git, Docker, Python, Emacs, tmux, Tailscale, etc.

Comparison with frameworks

For context, I benchmarked Oh My Zsh and Prezto on the same machine. To keep each test

isolated, I used ZDOTDIR and HOME to point ZSH

at a temporary directory with a fresh install, so nothing interferes

with the host config:

# example for Oh My Zsh

ZDOTDIR=/tmp/zsh-bench/omz HOME=/tmp/zsh-bench/omz \

zsh -i -c exitBoth frameworks were configured with minimal defaults: Oh My Zsh with

the robbyrussell theme and the git plugin,

Prezto with its standard modules (completion, prompt, git,

syntax-highlighting). Not entirely apples-to-apples since they ship more

features out of the box, but it gives a sense of the baseline cost.

Ignoring the first cold run (cache warming), the steady-state averages

were:

Oh My Zsh (default + git plugin): ~118 ms

Prezto (default modules): ~119 ms

My config: ~24 ms

To be clear, ~120ms is already a great result. Both frameworks should feel pretty fast for most people. The difference is only noticeable if you’re obsessive about shaving every millisecond, which I admittedly have a lot of fun doing…

~~~

Wrapping up

The techniques here are not exotic. Bytecode compilation, deferred initialization, precmd hooks, conditional loading, and caching. None of them are new ideas. The key is applying them systematically: measure, find the bottleneck, defer or eliminate it, measure again.

Again, this is just how I like to do things. Not everyone needs to write their own syntax highlighting or prompt. But if you enjoy being in control of every piece of your shell, it’s a rewarding way to work.

Links

- My dotfiles (26a4859), full configuration including ZSH

- A modular ZSH setup, the companion article covering the full config walkthrough

- ZSH documentation, the official reference